Melting point

- For the physical processes that takes place at the melting point, see Melting, Freezing and Crystallization

The melting point of a solid is the temperature at which it changes state from solid to liquid. At the melting point the solid and liquid phase exist in equilibrium. The melting point of a substance depends (usually slightly) on pressure and is usually specified at standard pressure. When considered as the temperature of the reverse change from liquid to solid, it is referred to as the freezing point or crystallization point. Because of the ability of some substances to supercool, the freezing point is not considered as a characteristic property of a substance. When the "characteristic freezing point" of a substance is determined, in fact the actual methodology is almost always "the principle of observing the disappearance rather than the formation of ice", that is, the melting point.[1]

Contents |

Examples

For most substances, melting and freezing points are approximately equal. For example, the melting point and freezing point of the element mercury is 234.32 kelvins (−38.83 °C or −37.89 °F). However, certain substances possess differing solid-liquid transition temperatures. For example, agar melts at 85 °C (185 °F) and solidifies from 31 °C to 40 °C (89.6 °F to 104 °F); this process is known as hysteresis.

The melting point of ice at 1 atmosphere of pressure is very close [2] to 0 °C (32 °F, 273.15 K), this is also known as the ice point. In the presence of nucleating substances the freezing point of water is the same as the melting point, but in the absence of nucleators water can supercool to −42 °C (−43.6 °F, 231 K) before freezing.

The chemical element with the highest melting point is tungsten, at 3683 K (3410 °C, 6170 °F) making it excellent for use as filaments in light bulbs. The often-cited carbon does not melt at ambient pressure but sublimes at about 4000 K; a liquid phase only exists above pressures of 10 MPa and estimated 4300–4700 K. Tantalum hafnium carbide (Ta4HfC5) is a refractory compound with a very high melting point of 4488 K (4215 °C, 7619 °F).[3] At the other end of the scale, helium does not freeze at all at normal pressure, even at temperatures very close to absolute zero; pressures over 20 times normal atmospheric pressure are necessary.

Melting point measurements

Many laboratory techniques exist for the determination of melting points. A Kofler bench is a metal strip with a temperature gradient (range from room temperature to 300 °C). Any substance can be placed on a section of the strip revealing its thermal behaviour at the temperature at that point. Differential scanning calorimetry gives information on melting point together with its enthalpy of fusion.

A basic melting point apparatus for the analysis of crystalline solids consists of a oil bath with a transparent window (most basic design: a Thiele tube) and a simple magnifier. The several grains of a solid are placed in a thin glass tube and partially immersed in the oil bath. The oil bath is heated (and stirred) and with the aid of the magnifier (and external light source) melting of the individual crystals at a certain temperature can be observed. In large/small devices, the sample is placed in a heating block, and optical detection is automated.

The measurement can also be made continuously with an operating process. For instance, oil refineries measure the freeze point of diesel fuel online, meaning that the sample is taken from the process and measured automatically. This allows for more frequent measurements as the sample does not have to be manually collected and taken to a remote laboratory.

Thermodynamics

Not only is heat required to raise the temperature of the solid to the melting point, but the melting itself requires heat called the heat of fusion.

From a thermodynamics point of view, at the melting point the change in Gibbs free energy (ΔG) of the material is zero, but the enthalpy (H) and the entropy (S) of the material are increasing (ΔH, ΔS > 0). Melting phenomenon happens when the Gibbs free energy of the liquid becomes lower than the solid for that material. At various pressures this happens at a specific temperature. It can also be shown that:

Here T, ΔS and ΔH are respectively the temperature at the melting point, change of entropy of melting and the change of enthalpy of melting.

The melting point is sensitive to extremely large changes in pressure, but generally this sensitivity is orders of magnitude less than that for the boiling point, because the solid-liquid transition represents only a small change in volume. [4][5] If, as observed in most cases, a substance is more dense in the solid than in the liquid state, the melting point will increase with increases in pressure. Otherwise the reverse behavior occurs. Notably, this is the case of water, as illustrated graphically to the right, but also of Si, Ge, Ga, Bi. With extremely large changes in pressure, substantial changes to the melting point are observed. For example, the melting point of silicon at ambient pressure (0.1 MPa) is 1415 °C, but at pressures in excess of 10 GPa it decreases to 1000 °C.[6] Melting points are often used to characterize organic and inorganic compounds and to ascertain their purity. The melting point of a pure substance is always higher and has a smaller range than the melting point of an impure substance or, more generally, of mixtures. The higher the quantity of other components, the lower the melting point and the broader will be the melting point range, often referred to as the pasty range. The temperature at which melting begins for a mixture is known as the solidus while the temperature where melting is complete is called the liquidus. Eutectics are special types of mixtures that behave like single phases. They melt sharply at a constant temperature to form a liquid of the same composition. Alternatively, on cooling a liquid with the eutectic composition will solidify as uniformly dispersed, small (fine-grained) mixed crystals with the same composition.

In contrast to crystalline solids, glasses do not possess a melting point; on heating they undergo a smooth glass transition into a viscous liquid. Upon further heating, they gradually soften, which can be characterized by certain softening points.

Freezing-point depression

The freezing point of a solvent is depressed when another compound is added, meaning that a solution has a lower freezing point than a pure solvent. This phenomenon is used in technical applications to avoid freezing, for instance by adding salt or ethylene glycol to water.

Carnelley’s Rule

In organic chemistry Carnelley’s Rule, established in 1882 by Thomas Carnelley, stated that high molecular symmetry is associated with high melting point.[7] Carnelley based his rule on examination of 15,000 chemical compounds. For example for three structural isomers with molecular formula C5H12 the melting point increases in the series isopentane −160 °C (113 K) n-pentane −129.8 °C (143 K) and neopentane −18 °C (255 K). Likewise in xylenes and also dichlorobenzenes the melting point increases in the order meta, ortho and then para. Pyridine has a lower symmetry than benzene hence its lower melting point but the melting point again increases with diazine and triazines. Many cage-like compounds like adamantane and cubane with high symmetry have very high melting points.

A high melting point results from a high heat of fusion, a low entropy of fusion, or a combination of both. In highly symmetrical molecules the crystal phase is densely packed with many efficient intermolecular interactions resulting in a higher enthalpy change on melting.

Predicting the melting point of substances (Lindemann's criterion)

An attempt to predict the bulk melting point of crystalline materials was first made in 1910 by Frederick Lindemann.[8] The idea behind the theory was the observation that the average amplitude of thermal vibrations increase with increasing temperature. Melting initiates when the amplitude of vibration becomes large enough for adjacent atoms to partly occupy the same space. The Lindemann criterion states that melting is expected when the root mean square vibration amplitude exceeds a threshold value.

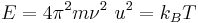

Assuming that all atoms in a crystal vibrate with the same frequency ν, the average thermal energy can be estimated using the equipartition theorem as[9]

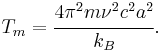

where m is the atomic mass, ν is the frequency, u is the average vibration amplitude, kB is the Boltzmann constant, and T is the absolute temperature. If the threshold value of u2 is c2a2 where c is the Lindemann constant and a is the atomic spacing, then the melting point is estimated as

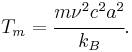

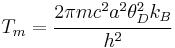

Several other expressions for the estimated melting temperature can be obtained depending on the estimate of the average thermal energy. Another commonly used expression for the Lindemann criterion is[10]

From the expression for the Debye frequency for ν, we have

where θD is the Debye temperature and h is the Planck constant. Values of c range from 0.15–0.3 for most materials.[11]

Open Melting Point Data

In February 2011[12] Alfa Aesar released over 10,000 melting points of compounds from their catalog as Open Data. This data has been curated and is freely available for download.[13] This data has been used to create a random forest model for melting point prediction[14] which is now available as a free to use webservice.[15]Highly curated and open melting point data is also available from Nature Precedings[16]

See also

- List of elements by melting point

- Phases of matter

- Triple point

- Liquidus temperature

- Slip melting point

- Solidus temperature

References

- ^ Ramsay, J. A. (1949). "A new method of freezing-point determination for small quantities". J. Exp. Biol. 26 (1): 57–64. PMID 15406812. http://jeb.biologists.org/cgi/reprint/26/1/57.pdf.

- ^ The melting point of purified water has been measured as 0.002519 ± 0.000002 °C, see R. Feistel and W. Wagner (2006). "A New Equation of State for H2O Ice Ih". J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 35 (2): 1021–1047. Bibcode 2006JPCRD..35.1021F. doi:10.1063/1.2183324.

- ^ Lide, D. R., ed (2005). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (86th ed.). Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0486-5.

- ^ The exact relationship is expressed in the Clausius-Clapeyron relation.

- ^ "J10 Heat: Change of aggregate state of substances through change of heat content: Change of aggregate state of substances and the equation of Clapeyron-Clausius". http://mpec.sc.mahidol.ac.th/RADOK/physmath/PHYSICS/j10.htm. Retrieved 2008-02-19.

- ^ E. Yu Tonkov, E. G. Ponyatovsky "Phase Transformations of Elements Under High Pressure", CRC Press, Boca Raton, 2005, p. 98 ISBN 0849333679

- ^ Brown, R. J. C. & R. F. C. (June 2000). "Melting Point and Molecular Symmetry". Journal of Chemical Education 77 (6): 724. Bibcode 2000JChEd..77..724B. doi:10.1021/ed077p724.

- ^ Lindemann FA (1910). "The calculation of molecular vibration frequencies". Physik. Z. 11: 609–612.

- ^ Sorkin, S., (2003), Point defects, lattice structure, and melting, Thesis, Technion, Israel.

- ^ Philip Hofmann (2008). Solid state physics: an introduction. Wiley-VCH. p. 67. ISBN 9783527408610. http://books.google.com/books?id=XfIpxi4kcM4C&pg=PA67. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ Nelson, D. R., (2002), Defects and geometry in condensed matter physics, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521004004

- ^ Bradley, J-C., (2011), Alfa Aesar melting point data now openly available

- ^ Open Melting Point Datasets

- ^ Bradley, J-C. and Lang A.S.I.D., (2011), Random Forest model for melting point prediction

- ^ Predict melting point from SMILES

- ^ ONS Open Melting Point Collection

External links

- Melting and boiling point tables vol. 1 by Thomas Carnelley (Harrison, London, 1885–1887)

- Melting and boiling point tables vol. 2 by Thomas Carnelley (Harrison, London, 1885–1887)

- ONS melting point explorer Over 10,000 Open Data melting points.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||